August 19, 2022

The just-concluded 2022 electoral process in Kenya was praised by many the world over.

It was smooth, serene and transparent with a vengeance. You’d think it was so as to exorcize all the demonic malpractices of the past. One of which, in 2007/8, saw the death of over 500 and wounding of more Kenyan kindred, apart from halting all business in the region.

The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) put all the votes on the public portal for anyone who cared to tally the votes, as they came in from constituencies. Seeing such clarity, some citizens who’d shuttered their business premises or gone into hiding were reassured by this calm openness and, so, life returned to its old bustle.

Many elective positions were up for grabs but, clearly, of most interest was the position of president of the republic. It was decidedly a two-horse race for the position, featuring the 77-year-old Raila Amolo Odinga and the 55-year-old William Samoei Arap Ruto. The ratings of two others were insignificant. The tight race kept keen followers on edge but, albeit a few skirmishes, all was going on well as the two presidential candidates headed for the finish line.

And then a nail-biting wait as the electoral officials went into hibernation for the final tally.

Alas, on emerging out, the seven officials were split three-four, spoiling what had been an orderly process! They could not agree on the tally.

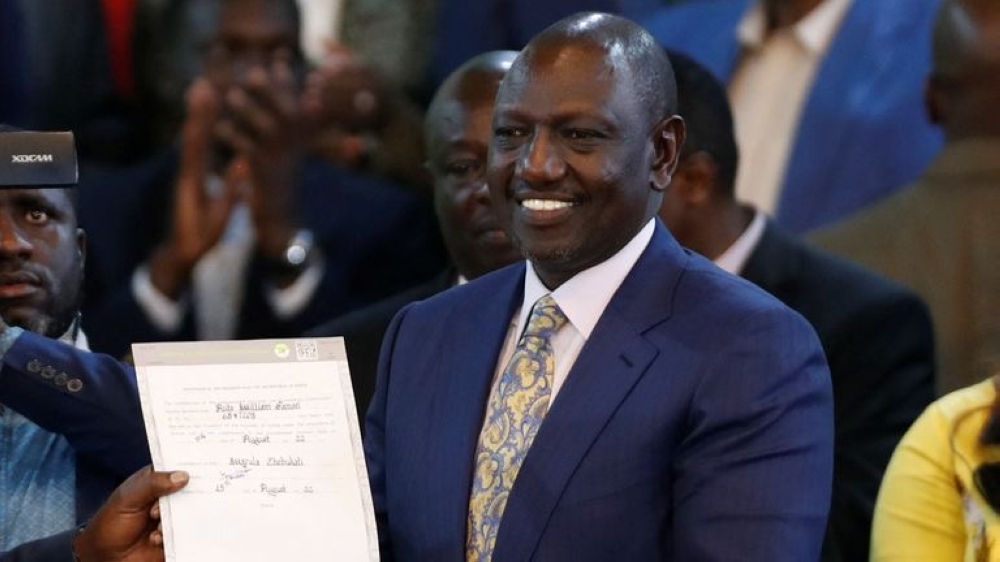

Still, The IEBC chairman, Wafula Chebukati, went ahead to announce Ruto as President of the Republic of Kenya. But Odinga would hear none of it and is bound for the courts.

Whatever the courts decide, let’s hope the calm that marked the electoral process prevails.

Generally, this election has been orderly so far, this time round.

But, in the first place, why should elections be cutthroat business in our countries, involving antagonistic and violent shouting matches, as if the candidates are not offering themselves to serve their people? Service which, in fact, should be sacrifice. If these candidates took this service as sacrifice, would they be at one another’s throat for it? If it’s a do-or-die affair, isn’t it for the interest of self rather than that of the people?

Moreover, as soon as this case is settled, the whole political class will be in feverish electioneering mode all over again. It’ll be a repeat of strategies being drawn on how to rearrange tribal and other blocks so as to garner winning numbers, so-called “tyranny of numbers”, for the next election!

Overall development of the country becomes a casualty in this case. Yet the raison d’être for all politicians should be to develop their countries and ensure the welfare of all the citizens.

So, why opt for this permanent state of agitation about elections, fearing for our lives? Why should we even find it necessary to applaud any country for not suffering a bout of electoral violence?

Why not choose the type of democracy that suits our context? Why not go for consensual democracy, among other available options, for example?

In a consensual democracy, as politicians you’d sit together to examine your country’s place in development, look at where you are coming from and determine where you want to go. Then strategize on how to reach there.

Whether you are in the ruling party or in any opposition party, you have a common denominator, which is that your aspiration all together is to see your country advance.

Your tactics of concretising your strategy and strategies of reaching your goals may differ, but that would serve to enrich the fertility of your ideas in the end. This, however, would perforce demand that you sit together so as to harmonise different ideas and hammer out a consensual conclusion.

As an African proverb says: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” Each of our African peoples want to go far. None of us as societies want to rush to nowhere!

Of course Rwanda has had to bear a lot of Western flak for choosing consensual democracy. But only she knows best the mistakes of her past. And, knowing the West’s stinking past – maybe present, too – what moral ground can they stand on to think that their writ can run in this country?

This is not to claim that competitive democracy cannot work in Africa, far from it. Africa is not lacking in examples where it has worked, limited as they may be. That, however, has been possible because politicians have relied on advancing good policies to outsmart their rivals. And the populace has been receptive only to the competition of practicable policies to guide their choices.

Otherwise, where politics risks veering into amassing numbers to win elections through the manipulation of ethnic, regional, religious and other groups, that inevitably breeds division. It’s this division that erupts into violence.

Which is why we should cheer Kenya for seemingly having abandoned those fractious considerations this time round, usually stoked by their politicians. It’s as it should be.

If we’ve made our antagonistic-democracy bed, now we must lie in it peacefully together.